"Follow me; I seek the everlasting ices of the north, where you will feel the misery of cold and frost to which I am impassive." — Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

The story of the Canadian Premier League in 2025 begins and ends in the snow.

Two clubs — Cavalry and Forge — stepped on the international stage in February's frosty Concacaf Champions Cup matches, but it wasn't until November that a CPL side really made news around the globe.

By now, hundreds of millions of people have encountered the scenes of the 2025 CPL Final; most have marvelled at David Rodríguez's so-called "icicle kick," which levelled the game en route to Atlético Ottawa's extra-time triumph.

Those who were at TD Place last Sunday, though, will remember more than the spectacle itself. Years from now, small moments from the hours spent at the stadium that day will pop into memory: "Remember when that happened?"

When the book is written on the founding and early steps of the Canadian Premier League, that Final in the snow will demand an entire chapter.

That chapter will read more like a fairytale than truth. At every turn, a new factor or moment added to the mythology of this one game.

Until the book is written, this is an account of Nov. 9, 2025 in Ottawa, Ontario — and a story of how Canadian perseverance put our soccer league in front of the world.

Isawitwassnowingandthought,'Todayisgoingtobeagoodday.'David Rodríguez

In the week leading up to the Final, the weather forecast for the capital region seemed to change every hour. From Monday to Wednesday, one to three centimetres of snow was the estimate for matchday — enough for a light dusting on the pitch, but unlikely to cause serious issues. For a while on Thursday, the latest projections threatened rain instead of snow.

By Friday night, however, the prognosis was clear: nine to 11 centimetres, with strong winds, beginning around midday and lasting until right when the Final would end (or was supposed to, anyway). In the end, it would be 11.7 centimetres — a new record for Nov. 9 in Ottawa.

Two days before the match, Atlético Ottawa goalkeeper Nathan Ingham shared that he and his team were relishing the likely conditions.

"There's a time in Canada where you shovel a rink in your backyard, and it's not quite cold enough to put the water down to flood it and turn it into an ice rink," said the Keswick, Ont. native. "For about three weeks, you can play soccer in that little area with your brother. We grew up here. It might be a bit of a messier game, but the beginning and end of every season you're going to get one game in the snow. If you're playing at the end of the season in the snow, it's a privilege."

That said, Ingham probably didn't expect to be shovelling off the turf himself. One of many iconic images from the Final came in the 16th minute, amid the first snow removal break, when Ingham grabbed a shovel and cleared off the penalty spot and corners of his box, in order to better orient himself within the goal.

But that's jumping ahead a little bit. Before Ingham even set foot on the pitch, there was a long way to go before this Final kicked off.

The morning of matchday, preparation continued at TD Place. In the preceding days, two snowplows had been made ready, and a bag of orange Derbystar balls tracked down. The stadium's grounds crew enlisted nearly 20 young volunteers to help with shovelling snow. Despite all the measures taken, though, an on-time kickoff was no guarantee.

Snow began falling in earnest around 1 p.m., and soon the pitch was fully coated. Shovellers and grounds staff equipped with leaf-blowers cleared off what they could, but the unrelenting fall from the sky made their work futile; a prematch ceremony rehearsal left bigger piles of snow on the field as it fell from the vast banners being unfolded.

Both Atlético Ottawa and Cavalry FC arrived around 3 p.m., and most players went straight out to the pitch to gauge the conditions. A few shook their heads, or pulled up their hoods to protect from the wind. Alberto Zapater, steeling himself for the final match of his 20-year playing career, had walked to the stadium. Shamit Shome, meanwhile, boldly walked out of the tunnel in shorts.

Footballers are usually stoic on matchday, particularly two hours before a final. On this occasion, though, members of both sides couldn't help but react, wide-eyed and eyebrows raised.

"This is going to be crazy," said a half-dozen players at varying intervals.

From at least a half-dozen more, though: "I can't wait."

Snowplows rolled out onto the field at 3:15 p.m., while the shovel crew trailed behind, desperately trying to clear away the large chunks left on the pitch. By the time Ingham, Tristan Crampton and Ottawa goalkeeper coach Romuald Peiser took to the pitch for warm-ups around 4:20, the plows had not yet cleared the whole pitch, but the Atleti penalty area already had a considerable new blanket.

The full Ottawa team emerged shortly after for their warm-ups, bundled up in tights and long-sleeve training tops, some players near-unrecognizable with their heads and faces covered too. Cavalry, meanwhile, trotted out of the tunnel, roughly half of them dressed in shorts.

Not to be outdone, Ottawa's equipment manager Bruce Hartill spent the entire evening in his hoodie, shorts and sneakers.

A brief conference between league staff, Canada Soccer officials, and both sides established a plan: the match would kick off 10 minutes behind schedule at 5:20. The shovels and leaf-blowers would be kept ready to keep the lines on the pitch as clear as possible, and the referee would be allowed to stop the match to ask for a snow removal break — estimated to be every 15 minutes.

By this point it was clear that this would be no usual soccer game. Clear also were the stakes: this was a final, with the North Star Cup and a place in the Concacaf Champions Cup on the line. Neither team would ever be content with the excuse of the conditions; they might not be able to play as they normally would, but both needed to find a way.

On a stage this big, the show must go on, and on it went.

In front of 13,132 fans, and thousands more watching on TSN and OneSoccer, the 2025 CPL Final kicked off in a blizzard.

"On a scale from one to 10, how sure are you that's the touchline?"

There's never been an atmosphere quite like it in the CPL. The Ottawa fans, many of whom were present in 2022 when Atleti lost a final at home, shouted above the howling wind to make themselves heard, including the above jab at an assistant referee.

David Rodríguez nearly beat Marco Carducci from 40 yards out in the second minute, and the crowd truly came alive; in these conditions, just one goal might be enough to win it all.

The problem wasn't just the snow — which piled on thick, so anybody not running around had to shake it off every couple minutes or so. Making things worse was the wind. Facing into it (as Atlético Ottawa were in the first half) meant a peppering of heavy snow pellets to the face, and it was nigh-impossible to lift your head fully and stare directly into the gusts.

Up and down the touchline, a camaraderie was forming between anybody mad enough to be at pitch level. Any photographer, ball kid or security guard had the same frozen, awed expression.

At one point, Cavalry assistant coach Jay Wheeldon walked up the sideline, shrugging: "I've never seen anything like it before," he said.

In a final, both teams will always look for any edge available, but the gamesmanship on this occasion started early. About 15 minutes in, during the first shovelling break, Ottawa's coaching staff noticed that Cavalry's substitutes weren't on the bench. The visiting side had sent them to the locker room to stay warm.

Furious, Atleti manager Diego Mejía shouted down the touchline at his opposite number — "You are a cheat," he lobbed at one point — but Tommy Wheeldon Jr. and his staff insisted they were breaking no rules. Still, fourth official Ben Hoskins ordered the Cavs to bring their subs back out. They complied — slowly — but as they emerged from the tunnel, sheepish grins on their faces gave away that they might've expected the scolding.

Cavalry took the lead shortly after from the penalty spot; Fraser Aird's bare-knee slide through the snow might've been the front-page photo from this match had that been the last of the drama.

David Rodríguez, however, had other ideas.

The 23-year-old native of San Luis Potosi, Mexico, had seen snow just once before in his life: from a car window, shortly after landing in Ottawa in February. Sunday's game was the first time he had set foot in it.

Rodríguez had come away from Friday night's CPL Awards gala somewhat disappointed — he left empty-handed after a remarkable debut season, and although he fully endorsed his teammate Sam Salter's sweep of the Player and Players' Player of the Year awards, he still had a point to prove.

While players around him trudged through the snow, he danced across it, willing the ball to go with him.

By the 40th minute, the playing surface more resembled a beach than a football pitch, and even Rodríguez struggled to play the ball on the ground.

To the air instead, then. A ball skipped up in front of Rodríguez after a Gabriel Antinoro volley into traffic in the box, and he opted for the audacious. His bicycle kick smacked off the crossbar and in, and even the fans needed a second to process the moment — those at the other end of the pitch could hardly see what exactly Rodríguez had done.

A horde of photographers sprinted down the touchline, eager to capture some small piece of the celebration after the greatest goal ever scored in the CPL.

The crowd, stunned into silence when Cavalry took the lead, came right back to life. When the sides went into halftime tied, the home side had the momentum. So much so, in fact, that it felt more like they'd taken the lead than equalized.

"Everyonefeltliketheywereinthemoment.There'snophonesout;everyonehadgloveson.Itfeltlikeeveryonewasjusttogether,moresothanI'vefeltatasportingeventinalong,longtime."Nathan Ingham

The second half was a slog. By that point — around 6:30 p.m. — the storm was at its peak; sheets upon sheets of snow continued to fall on the pitch, faster than the shovellers could keep up. There was no use in plowing the field again; the rate of snowfall meant it made more sense to keep the penalty areas and lines clear and get the players back on the pitch.

With at least an inch-thick layer of snow now coating the field, the game now barely resembled the sport these sides had been playing all year. The ball would stick when it fell; slide tackles carried on for metres; players had to adjust the way they received passes, halting their runs rather than continuing forward and waiting for the ball to meet them.

By now, shovellers were clearing snowbanks away from the touchlines even during play to keep them from spilling onto the field.

Neither team was getting close to scoring again, even when they got the ball into the box; both sides had plenty of chances, having learned to play it long and create chaos, but it was hard to get any power on a shot.

Those on the sidelines were numb to the cold; anybody who hadn't been smart enough to lift their coat's hood an hour earlier now couldn't do so without pouring a full snowdrift down their back.

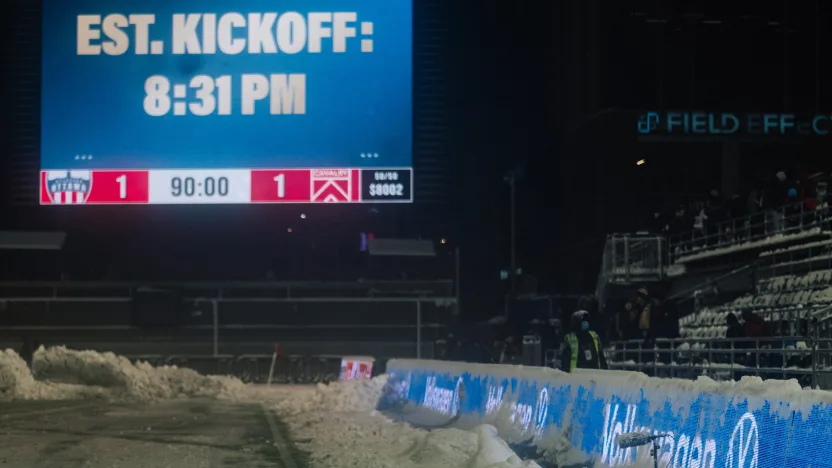

If the game needed more than 90 minutes (and it did) there were two options: forego extra time and head straight to a penalty shootout, or take enough time to plow the pitch entirely before playing the 30 minutes. At last, the blizzard had peaked and the wind was dying down, so it might actually be possible to clear much of the snow.

Neither team wanted penalties, so back came the snowplows.

The clubs knew the delay would be a long one, so they retreated to dressing rooms for a brief respite from the cold. Cavalry fully embraced the wait; they sought to warm up as much as possible, changing out of their kits. A few players even spent the delay in the visiting locker room's hot tub.

Ottawa, meanwhile, took a different approach. They were instructed to stay loose, and warm up — but not too warm. Mejía chose not to even address his team during the break.

Up in the stands, the faithful spectators did not have the luxury of a warm locker room, and there's certainly no hot tub in the concourse at TD Place. Some of Ottawa's players, including Ingham, had spoken in favour of going straight to penalties just to allow the fans to get out of the cold sooner.

Those seated in the north stand, however, were able to take refuge in the attached hockey arena below the seats of TD Place. Players in that night's beer league game might have been surprised to see several hundred soccer fans watching them, but the Atleti fans were grateful for a distraction during what might otherwise have been a very nervous break.

It was around this moment that word began to get around about just how much of the internet was talking about this CPL Final. The league was the number one trend in Canada on X; news outlets and accounts from all around the world had caught on to Rodríguez's goal.

Canadian soccer, too often a footnote in the global game, was now in the spotlight. And thirty minutes still remained to crown a champion.

One hour, eight minutes and 39 seconds after the original 90 minutes ended, Sam Salter kicked off to begin extra time.

It was like a reward for getting through the first two halves.

These two sides, both so deserving of their shot at a championship, had battled without much complaint through the harshest conditions they’d ever played in. The snow had stopped, the wind calmed, and the full pitch was clear and visible.

Now, with the North Star Cup on the line, they’d have half an hour to play real football.

It was with smiles on their faces — less incredulous than before the match — that both sides emerged.

Ottawa coach Diego Mejía had spoken all year about how talented his team was, and how unique their attack-minded style of play. With so many eyes on them in the Final, they hadn’t been able to truly show it until now. The home side were clearly the better of the two when play resumed, too. Sensing an impending moment, the majority of the match's photographers and videographers gathered in the Cavalry half.

At 105 minutes, unlike the usual routine for an extra time match, referee Michael Venne blew his whistle and ordered the two teams to swap sides immediately, then kick off again. With the game already running so long, why waste any longer?

Now that Ottawa were attacking to the west, with the (weaker) wind at their backs and the Capital City Supporters' Group in Section W willing the ball into the net in front of them, Atleti suddenly looked inevitable.

The crowd was restless, though; even Wally the Dinosaur, Ottawa's beloved mascot, knocked over an ad board by the pitch in protest of a foul not given Atlético's way.

Just two minutes after the change of ends, David Rodríguez came through again.

As soon as the Mexican winger chased down Manny Aparicio's long pass, the crowd leapt right to its feet. No longer afraid the ball would stick in the snow or stop dead, this was a situation they'd seen so many times this year: David Rodríguez, one-on-one with a goalkeeper.

It's a finish that, in hindsight, deserves more credit than it got. Rodríguez's chip over Carducci was so perfectly-placed that it looked easy. That has been his trademark all season, though; Rodríguez can do things on a football pitch that few others can, and it couldn't have been anyone but he who played the hero for Ottawa.

He wasn't wearing a cape, but he might as well have as he lost his footing and dived, arms outstretched and head-first, into the snowbank behind the goal.

"[Rodríguez]wastellingmeinthechangingroombefore,andactuallyallgame:Whenyougetit,putitintospaceandI'llgetthere."Manny Aparicio

For the final 13 minutes, Atleti went into protection mode. They'd probe for another goal, but above all they couldn't afford to make any mistakes or give the ball away cheaply on a pitch that, while much better than before, still didn't offer the surest footing.

When Gabriel Antinoro took the brunt of a tackle in the 116th minute, incensed screams rose from the Ottawa bench, who wanted Goteh Ntignee sent off. Lost in the furor, though, was one of Ottawa's staff instructing his players to make sure Antinoro stayed on the pitch for treatment, to keep the game stopped. Loïc Cloutier thus dragged his teammate by his feet from the ad board back over the touchline, while the referee was busy showing Ntignee a yellow card.

The four minutes of added time were interminable; Mejía repeatedly screamed for the final whistle, but Cavalry kept cycling the ball back into Ottawa's half. They only played 24 seconds beyond the four — enough for just one ball into the box, which Ingham collected — and at last it was over.

At 9:10 p.m., just under four hours since the match began, Atlético Ottawa won their first CPL championship.

Within moments, the team had Zapater up on their shoulders. Shortly after that, it was Mejía.

Several thousand brave fans who had stuck it out were vindicated for doing so; the first place Atleti's players went after receiving the North Star Cup was to Section W, to share the victory with their supporters. In fact, celebrating with the fans took so long that eventually, Ingham ran into the dressing room to collect a handful of beers and get the party really going.

Soon enough, the Ottawa players were back in the dressing room, where they finally received their medals, and Rodríguez picked up his CPL Final MVP prize — that part of the trophy ceremony had been skipped on the pitch to move things on faster. It was in that room, finally, that the team allowed themselves to reflect not just on this spectacular night, but on an incredible 2025 season.

Zapater, having won his second ever trophy in the last stanza of his career, was the quietest of the group. He stood on a seat in the corner, gazing over his jubilant teammates, breaking his silence just a few times to speak with his co-captain Ingham — with whom he'd shared the first hoist of the North Star Cup.

Meanwhile, shortly before the bottles popped, Kevin Dos Santos called out a familiar line of Mejía's from throughout the season: "Best team in the history of the CPL!"

"Now I can say it?" Mejía, champagne in his hand, called in response.

Moments after the final whistle, Rodríguez took a solo lap of the pitch. Draped in the Mexican flag, he allowed tears to stream down his face — or perhaps they froze halfway down.

Two hours later, he sat once again out in the snow, accompanied by the North Star Cup, the Final MVP trophy, an empty bottle of champagne and his girlfriend Emely. He posed for photos, but still took another moment for himself.

He didn't know what was next. On loan with Ottawa from sister club Atlético de San Luis, he might have played his final game in the CPL.

Amid the excitement, Rodríguez did say a few times that he'd see us in Concacaf next year — but it may not be entirely up to him. After a remarkable year in Canada, clubs across the continent and abroad will soon come calling. There's no doubt he could play in Liga MX or MLS in the near future.

If, indeed, his journey in Canada ends here, then what better way for it to end than in the most Canadian conditions?

Without the contributions of Rodríguez, a Mexican-American who fully embraced the world of Canadian soccer, this CPL Final would not have been the same. Memorable, of course — though it was guaranteed to be memorable at least an hour before kickoff.

In a different world, the Final goes differently; perhaps Aird's penalty is the only goal, and Cavalry grind their way to a second-straight championship. Perhaps Ottawa find a way back. Maybe scenes from the game, like Ingham shovelling, still go viral, and give the CPL a brief moment in the spotlight.

That's not how it played out, though. Instead, one iconic moment will live forever in this sport's lore. The "icicle kick" will stick in the dialect of Canadian soccer fans. It could pop up again this time next year on FIFA's Puskas Award shortlist.

And Ottawa will not soon forget David Rodríguez, who spent just one season there.

Years from now, when the sport explodes across Canada in the wake of a World Cup on home soil, many will recall the profoundly Canadian scenes of that 2025 CPL Final.

And those lucky enough to be at TD Place that night will be able to say:

"I was there."